In the US, class action litigation has long been a common method for people to seek redress when they have been injured in a common manner by common defendants. This also applies to shareholders. In response to the many accounting scandals of the past five years, a large number of accounting-related securities class action lawsuits have been filed. This year, US$ 6 billion is expected to be awarded to investors in US companies, as a result of settlements relating to companies such as Worldcom, McKesson and Adelphia. The biggest settlements over the past few years include Cendant (US$ 3.5 billion), Worldcom (US$ 2.6 billion), Lucent Technologies (US$ 517 million) and Raytheon (US$ 460 million)1 . Given the economic significance of the settlements in securities class actions it is worth addressing the issue. In the next sections we will start off with a short description of the class action process as it operates in the US, followed by a brief overview of the major trends. Then we will discuss the different forms of (proposals for) class action litigation outside the US, followed by a discussion of how pension funds should deal with class action litigations as part of their corporate governance policies. We will end this article with a discussion of the pros and cons of being a lead plaintiff.

In the US, class action litigation has long been a common method for people to seek redress when they have been injured in a common manner by common defendants. This also applies to shareholders. In response to the many accounting scandals of the past five years, a large number of accounting-related securities class action lawsuits have been filed. This year, US$ 6 billion is expected to be awarded to investors in US companies, as a result of settlements relating to companies such as Worldcom, McKesson and Adelphia. The biggest settlements over the past few years include Cendant (US$ 3.5 billion), Worldcom (US$ 2.6 billion), Lucent Technologies (US$ 517 million) and Raytheon (US$ 460 million)1 . Given the economic significance of the settlements in securities class actions it is worth addressing the issue. In the next sections we will start off with a short description of the class action process as it operates in the US, followed by a brief overview of the major trends. Then we will discuss the different forms of (proposals for) class action litigation outside the US, followed by a discussion of how pension funds should deal with class action litigations as part of their corporate governance policies. We will end this article with a discussion of the pros and cons of being a lead plaintiff.

The process of class action litigations

In the US, securities class actions are usually initiated by large institutional investors who suffered a loss on a particular stock or by specialist law firms, which typically pocket 25 percent of any settlement they secure (given the size of the settlements over the past few years, most law firms have had to trim their share of the pie). Normally one of the investors, who have suffered the biggest loss, takes the lead in the class action by taking the role as lead plaintiff. This follows from the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (PSLRA) of 1995. The ‘lead plaintiff appointment’ provision of the PSLRA in 15 USCS §78u-4(a)(3), provides that within 60 days after the publication of the filing notice of the initial securities class complaint, any person or group of persons who are members of the proposed class may apply to the court to be appointed as lead plaintiff. The court shall appoint as lead plaintiff the member or members of the class that the court determines to be most capable of adequately representing the class members’ interests. In determining the ‘most adequate plaintiff’, the PSLRA provides that the presumptively most adequate plaintiff is the investor with the largest financial interest.

Under US law, all investors who held stock during the qualifying period automatically become members of the class action and are entitled to collect their share of any awarded damages. Shareholders do not have to spend a dollar or appear in court; they simply have to register to receive an award. There may be situations in which an investors thinks that his interests are better served outside the class. In that case he has to file a request at the court to opt out of the class. This way the investor retains the right to start his own lawsuit (we will discuss the pros and cons of being a lead plaintiff later).

To claim part of a settlement, investors must contact the claims administrator, who is appointed by the court after a settlement is announced. Once the settlement is agreed, investors have 90 days to register a claim or lose their entitlement. After registration of their claim, investors are sent forms that they have to fill out and return to the administrator (these forms contain information on the position in the stock during the qualifying period and the loss suffered on the position). For institutional investors it is common that they outsource all these activities to specialized firms like for example IRSS.

Trends in shareholder class action litigation in the US

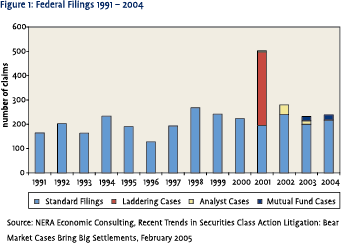

Given the increased media attention for class actions over the past few years, it seems as if the number of class actions has increased significantly. This is, however, not the case. Figure 1 presents an overview of the number of federal filings over the period 1991 – 2004. If we would leave out the 303 laddering cases (cases against IPO’s – generally against companies and their underwriters that allocated shares in ‘hot’ IPOs in exchange for excessive and undisclosed commissions, and for investor guarantees to purchase additional shares in the after-market) in 2001, the 54 cases against financial analysts in 2002/03, and the 39 cases against mutual funds in 2003/04, we find that the number of filings has actually been rather stable over time. Some people were expecting a rise after the implementation of Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX), since it extends the statute of limitations to two years (from one year) after the discovery of a violation and to five years after its occurrence (from three years).

Given the increased media attention for class actions over the past few years, it seems as if the number of class actions has increased significantly. This is, however, not the case. Figure 1 presents an overview of the number of federal filings over the period 1991 – 2004. If we would leave out the 303 laddering cases (cases against IPO’s – generally against companies and their underwriters that allocated shares in ‘hot’ IPOs in exchange for excessive and undisclosed commissions, and for investor guarantees to purchase additional shares in the after-market) in 2001, the 54 cases against financial analysts in 2002/03, and the 39 cases against mutual funds in 2003/04, we find that the number of filings has actually been rather stable over time. Some people were expecting a rise after the implementation of Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX), since it extends the statute of limitations to two years (from one year) after the discovery of a violation and to five years after its occurrence (from three years).

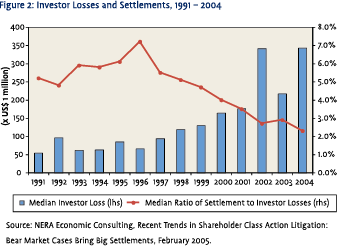

As noted before, the heightening of public anger at firms following the accounting scandals of Enron, Worldcom, Global Crossing and others has had little if any impact on the number of filings. What has changed, though, is the median investor loss over the past years. Figure 2 shows the median investor loss over the period 1991 – 2004. Since 1996 there has been a substantial increase in the median loss (by focussing on the median loss instead of the average loss we reduce the upside bias resulting from a few large cases, e.g. Enron and Worldcom). Interestingly, the sharp increase in investor losses has not been followed by a comparable increase in the size of the settlements. Over the period 1991 – 2002 the median ratio of settlements to investor losses fell from about 5% to around 2%.

Although the recovery rates seem quite low – and falling – one has to bear in mind that especially over the past five years, recovery rates tend to be understated. First, the legally compensable loss is typically substantially less than the investor losses relative to the S&P 5003. And second, since many shareholders eligible to claim under the class settlement agreement do not do so, those investors who file claims typically get twice their pro rata share of the settlement amount (most settlements are fixed in value and distributed pro rata to shareholders filing claims). In so far these non-claiming investors include institutional investors we can question their fiduciary responsibility; we will come back on that later.

Although the recovery rates seem quite low – and falling – one has to bear in mind that especially over the past five years, recovery rates tend to be understated. First, the legally compensable loss is typically substantially less than the investor losses relative to the S&P 5003. And second, since many shareholders eligible to claim under the class settlement agreement do not do so, those investors who file claims typically get twice their pro rata share of the settlement amount (most settlements are fixed in value and distributed pro rata to shareholders filing claims). In so far these non-claiming investors include institutional investors we can question their fiduciary responsibility; we will come back on that later.

Another interesting trend is the growing number of class action settlements that have included corporate governance reforms in the settlement terms. Examples include the settlements of Honeywell, Mattel and Sprint. In the settlement terms of Honeywell it was stated that measures needed to be taken to ensure the independence of outside auditors and the board of directors. The settlement of Sprint included a term that reduced directors’ terms to one year from three years. The corporate governance reforms included in the settlement terms of Mattel were not disclosed.

A last trend worth mentioning is the growing number of institutional investors that require executives to take their responsibility and pay portions of settlements out of their own pockets. This was the case with the settlements of Enron and Worldcom, which we see as a positive development, since in the current situation, damages are paid by the shareholders (damages reduce the firm’s free cash flow; even when part of the damages are covered by D&O insurance – which excludes cases of fraud – this will lead to higher insurance premiums, the burden of which will be on the shareholders).

Developments on forms of class action litigation outside of the US

In the Dutch legal system we also have class action litigation. Since the beginning of August 2005 we have a new law – known as the Wet Collectieve Afhandeling Massaschade – that makes a settlement binding for all members of a class who do not specifically opt out from a settlement. Recently, the new law was applied in the ‘Dexia-aandelenlease’ case. In 2004, France began contemplating legislation that will allow class action lawsuits to proceed in French courts. The initiative came from France’s President, Jacques Chirac. A formal proposal is not yet submitted to the French parliament but it is expected before the end of the year.

There are indications that the German government is considering an American style of class actions in response to a growing number of corporate frauds (given the upcoming elections it is rather uncertain whether steps in this direction will be taken in the coming years, if ever). An important trigger was the recent litigation against Deutsche Telekom. In that case, some 15,000 individual claims were filed with a court. Because German law requires that each case be litigated separately, claims of this type, which are becoming more commonplace, will need to be managed more effectively and more efficient, otherwise the German legal system will end up in an unprecedented logjam of cases.

In 2000 the UK introduced possibilities for group litigation. Unlike the US, this system is based on an ‘opt-in’ principle, which means that no investor is a class member unless he explicitly notifies the administrator that he wants to be included in the class. Australia has a similar ‘group litigation’ system. Similar developments as in The Netherlands, France and Germany, are going on in Italy, Sweden, Finland, Norway and South Korea. In spite of the possibility for a growing number of investors to start a class action lawsuit in their own country, it is to be expected that most investors will have a preference for the US, as settlements in the US are more generous than in most other countries.

Class action litigation and corporate governance

Class action lawsuits are filed against companies, their directors and/or officers because of alleged breaches of fiduciary duties to shareholders. In such cases where it has suffered damages, an investor has a claim with a certain value that can be considered an asset. Good governance requires institutional investors, including pension funds, to take all reasonable steps to realize such a claim, as it follows directly from their fiduciary duty.

A study by Cox & Thomas (2002) shows that only 28% of institutional investors actually filed claims in class action settlements in the US. This number is very low considering that in 2004, securities fraud class action settlements produced about US$ 5.5 billion in cash to be distributed to defrauded investors. Pullen (2005) estimates that on average between US$ 1 billion and US$ 2 billion is left on the table due to institutional investors who do not claim their settlement monies. The money that’s left on the table by European institutional investors is even worse. According to Tucker (2005), more than US$ 2.4 billion that had been awarded to European investors in US companies – or 95% of the total – went unclaimed.

In January 2005, in a landmark case, policyholders filed a US$ 2 billion damages claim against 44 US mutual funds, including Merrill Lynch and Janus, for allegedly failing to file class action claims to recover settlements money for the funds’ shareholders. The courts have yet to rule on whether they had a fiduciary duty to file class action claims. Irrespective of the ruling in this case, the issue served as a reminder of the risks involved in not acting.

Lead Plaintiff and opt-out considerations

In case an institutional investor has suffered a significant loss, it may consider to take the role of lead plaintiff. Being a lead plaintiff as an institutional investor has some pros and cons. A first advantage is that in cases where an institutional investor acts as lead plaintiff, awarded damages are about 20% higher than in case of an individual acting as lead plaintiff (conform the findings of Cox and Thomas, 2005). Secondly, institutional investors typically pay lower attorney fees than individual plaintiffs. The standard fee in securities cases is around 30 percent, however large institutional investors usually are able to bring down that cost substantially. Obviously, this is in the interest of all class members. The two advantages just described focus on the general benefits of an institutional lead plaintiff over an individual lead plaintiff. In addition to that we like to mention two advantages that an institutional investor can capture by becoming lead plaintiff. First, it may be beneficial for the institution’s image in the market. Acting as lead plaintiff is deemed to be one of the easiest, least time-consuming and least expensive ways of being an activist. Second, it has been shown that expected revenues for the lead plaintiff are normally higher than for the ordinary class members.

There are, however, also some drawbacks of being a lead plaintiff. First, acting as a lead plaintiff may involve certain reputational risks. If the class is not going well and the lead plaintiff is receiving a lot of negative media attention, this may hurt the institution’s reputation. Second, being a lead plaintiff can lead to trade restrictions. It sometimes happens that lead plaintiffs get information that is not publicly available, which prohibits him from trading in the firm’s securities. Third, monitoring the class action, which is a prime task of the lead plaintiff, can be relatively costly and time-consuming. Fourth, a lead plaintiff will be the fiduciary of the class for purpose of conducting the case. This merely means that the lead plaintiff must make decisions concerning the case with the best interests of the class members in mind. The lead plaintiff cannot just pursue its own interests. This can be a problem in case the various class members have different interests. A pension fund, as a long-term investor, may want the firm to improve its governance structure, whereas another (private) investor is only interested in a maximum recovery, irrespective of the interests of current and future shareholders. Finally, a lead plaintiff can be subject to discovery. This usually requires the production of the file regarding the investment in question. For most institutions this is a small amount of documents. However, the person or people responsible for the investment will usually have to give a deposition about their reasons for making the investment. This is the primary inconvenience of serving as lead plaintiff.

Before opting for lead plaintiff an institutional investors has to make his own cost-benefit analysis taking into account all issues discussed above. Sometimes an investor’s interests are better served outside the class. In that case he has to request the court to opt out of the class. Opting out typically can be beneficial if:

- the investor’s interests do not align with the interest of other members of the class;

- the investor has a basis to fear that the lead plaintiffs and lead counsel for the class do not have his best interests at heart;

- the investor has a separate claim which is not covered by the class complaint;

- ‘the class’ made disadvantageous arrangements respecting fees and expenses;

- there are unusual facts that suggest a benefit to independent non-class litigation.

Conclusions

In this article we have discussed the process of class action litigations. As we have shown it is not very difficult or time consuming to become a class member. Even more, given the significant destruction of shareholder value due to accounting fraud that we have seen over the past five years, there is plenty of reasons to pay attention to and have a policy on securities class action litigation. We also noticed that from a corporate governance perspective institutional investors have a fiduciary obligation to realize any claims that result from securities class actions. If they do not act properly, they leave money on the table that belongs to their clients.

For certain institutional investors, especially the bigger ones, it might under certain conditions be interesting to take the role of lead plaintiff. Usually there are some economic benefits that a lead plaintiff can realize and it may also be beneficial for the institution’s reputation. However, there are also costs and risks involved, with the main risk being reputational risk (in case the class action leads to a disappointing result). An institutional investors should therefore, balance all pros and cons before deciding on its role in a class action.

Noten

- NERA Economic Consulting, Recent Trends in Shareholder Class Action Litigation: Bear Market Cases Bring Big Settlements, February 2005.

- The lead plaintiff provision was adopted in order to encourage institutional investors to become the class’ representatives with the expectation they would actively monitor the conduct of a securities fraud class action so as to reduce the litigation costs. In a recent paper Cox and Thomas (2005) have examined, whether institutional investors are indeed a more effective monitor of securities class actions. They found that institutional investors more frequently act as lead plaintiff since the introduction of the PSLRA, although their focus is mainly on the bigger cases. They also found that the presence of an institutional lead plaintiff is positively correlated to the size of the settlements.

- This was especially the case in the bear market of 2000- 2002. During that time there was a significant performance difference between the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq. Of course, this contributes to the losses suffered by investors in Tech stocks.

- This section is partly based on the Schiffrin & Barroway Bulletin, Spring 2005.

- Obviously, this only applies to stocks that have a listing in the US.

Literature

- Buckberg, E., T.S. Foster, R.I. Miller and A. Werner, Recent Trends in Securities Class Action Litigation: Will Enron and Sarbanes-Oxley Change the Tides?, NERA Economic Consulting, June 2003

- Buckberg, E., T. Foster, R. Miller and S.Plancich, Recent Trends in Securities Class Action Litigation: Bear Market Cases Bring Big Settlements, NERA Economic Consulting, February 2005

- Check, D.J., Governments around the world consider and develop forms of class action litigation, S&B Bulletin, Spring 2005

- Cox, J.D., R.S. Thomas, Leaving Money on the Table: Do Institutional Investors Fail to File Claims in Securities Class Actions?, Washington University Law Quarterly, No. 80, p. 855-81, 2002

- Cox, J.D., R.S. Thomas, Empirically Reassessing The Lead Plaintiff Provision: Is the Experiment Paying Off?, Vanderbilt University Law School, Working Paper 05-21, 2005

- Tucker, S., Time to claim your slice of the pie, Financial Times, 19 May 2005

in VBA Journaal door Hans de Ruiter